Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory (PDF)

“Where Three Trails Meet on Boston Common: ROBERT GOULD SHAW and 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment Memorial”

Nancy Scott

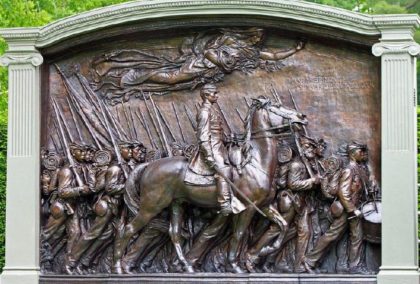

The ROBERT GOULD SHAW and 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment Memorial is the one singular site in Boston where the Freedom Trail, the Black Heritage Trail, and the UUA Walking tour all meet. Each of these history tours evoke specific events and, notably, the colonel – the freed slave as soldier – the artist – and the larger communities they symbolize. The Shaw Memorial represents a site of commemoration, one of America’s greatest public sculptures, a concentration of artistry, pride and a barometer to our ongoing struggles with the legacy of slavery. The bronze relief faces the Bulfinch State House with its golden dome surmounted by a pine cone, from the public ground of the Boston Common. The memorial faces the seat of government and serves as a constant reminder of where we stand now.

The power of its placement is no small matter; in fact Robert Gould Shaw’s sister Josephine Shaw Lowell (Effie) insisted that the memorial should stand on the people’s ground. The three trails that meet at the Shaw and 54th Massachusetts Memorial on the corner of Beacon Street all reflect also on important histories: the legacy of Emancipation in 1863, the brutal division of Civil War, and ongoing elements of racism and white supremacy that have broken through from our nation’s past ills. Monuments and memorials have come to the center of much of this debate, as we all know.

It was once citizens who slowly brought this great artwork into existence from the 1860s until its inauguration on May 31, 1897. The abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass is absent from the memorial, but it was he who exhorted, published, and forcefully symbolized the call for African-American soldiers. His advocacy stands behind the representations of the soldiers, as Douglass went personally to encourage Lincoln to embrace the controversial strategy of accepting African-American volunteers into the Union Army, especially to yoke the cause of Union with the anti-slavery position. Ultimately, given the heroic charge of the 54th Massachusetts at Fort Wagner in July 1863, more than 200,000 black soldiers would serve, and have been credited with adding force to the final push to victory.

The monument is deeply meaningful to many; it inspired poetry immediately, from James Russell Lowell and Ralph Waldo Emerson (Voluntaries, 1863); during World War II, John Berryman saw a homeless man sheltering on a wintry night at the monument and wrote Boston Common; Robert Lowell penned For the Union Dead in 1960, upset by many civic and national issues of the era.

Then, there is the early 20th century music of Charles Ives (Three Places in New England, 1911-14), the first part of which is “St. Gaudens in Boston Common.” The entire saga of Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts became the movie Glory, in 1989, which details their excited anticipation and tragic fate, coming from Ohio, Pennsylvania and elsewhere to join the Massachusetts regiment – and then, fighting against all odds at Fort Wagner in South Carolina. As Rev. Heather commented to me, the monument continues to do its work.

Robert Gould Shaw’s family wanted no monument at all. The default mode, a grand equestrian for their fallen son and brother, appalled the family, and they instead created a school for black children in Charleston, South Carolina. Robert Lowell’s poem recalled tersely: “Shaw’s father wanted no monument / except the ditch.”

Only fifty-seven portrait photographs, many tintypes, remain as documents of the soldiers themselves, taken before their departure from Camp Meigs where they trained – in what is today Hyde Park. These were reconstituted in a 2013 exhibition at the National Gallery “Tell it with Pride.”

Two decades later the aesthetic imagination of the artist Saint-Gaudens re-created their march out from Boston to the harbor ship which took them to fight in South Carolina, even as he dreamed of shaping the young colonel in full three- dimensions on his horse, parallel to his soldiers. In retrospect, this hierarchy has been much debated.

Robert Lowell saw Shaw differently: [FOR THE UNION DEAD, (1960)]

“Its Colonel is as lean

as a compass-needle.

He has an angry wren like vigilance,

a greyhound’s gentle tautness;

Saint-Gaudens bestowed upon these soldiers an enduring presence, even though he drove the Boston memorial commission to despair as they waited for fourteen years. As the vigorous debate suggests, this was and remains a living monument. There are twenty-three soldiers marching out with their canteens and shouldered rifles. These were distilled from the modeled heads of forty individual African-American men and boys, chosen in order to reflect the individuals of the unit, known from those few remaining photographs of the 54th, both soldiers and drummer boys. They literally were modelled forward during Saint-Gaudens’s process, so that he continued to lift them to the nearly three-dimensional depth they occupy. He coaxed, paid, and brought the models to be sculpted in his NY studio with an increasing ease and camaraderie as the project evolved.

Many of these African – American citizens were suspicious, later proud; Saint-Gaudens himself literally transformed his own view. From his freedom in sculpting the heads of these soldiers, we have the first American monuments with standing black soldiers, a clear demarcation from the ‘kneeling slave’ motif of earlier Civil War works. [One of these is the Lincoln Emancipation monument in Park Square.] The engrossing sympathy for both the youngest and older soldiers shows the artist’s realist style, yes, but also his deep connection.

If you go again to the Shaw memorial, look at details such as the first drummer juxtaposed with the solemn bearded man just behind, the rhythmic union of their marching legs, the wrinkle of leather and the button boots, the detail of pine branches and cones to the far left by the last soldier. The pine is the symbol of remembrance.[1]

The allegory of Memory floating above the soldiers drove the artist, and everyone waiting, to distraction. Saint-Gaudens modeled her endlessly – she carries a bundle of poppies with the olive branch, symbols of peace and sleep, her floating arm extended forward over the soldiers. Saint-Gaudens remodeled her for the fourth and last time, even after the 1897 inauguration of the bronze, for the plaster version to be shown in Paris; [This last version is today exhibited in the National Gallery, Washington D. C., on long term loan from the Saint-Gaudens Historic Site in New Hampshire.] The Boston committee, fuming over the many artistic delays, called her “that Devil Angel.”

None of my remarks are meant to gloss over the continuing racism and despair that the monument has also reflected: neglect. Effie Shaw Lowell had insisted on naming all the soldiers on the monument at the origins; they were not inscribed until 1982. It all took another civic intervention, and today the African- American soldiers’ names are visible, if carved below the five wreaths originally carved in honor of the five white officers. Their names were never given priority, and the monument has occasionally suffered vandalism, including yellow paint thrown on its surface as recently as 2013.

In 1897 at the time its inauguration, the monument was unveiled just as racial issues resurfaced with the rise of ‘Reconciliation.’ This is the very decade when the Lost Cause movement strengthened, and its monuments, often with soldiers high atop columns or pedestals, began to appear all across the South, even in border states such as Kentucky and Maryland. Like democracy, the Shaw memorial has needed much civic attention.

Critics, art historians, and prominent figures alike have named the Shaw and 54th Massachusetts Regiment memorial as the most remarkable piece of American public sculpture. It can been argued that this is ultimately an anti-war memorial; we sense the danger awaiting this march, and there is no echo of the single heroic act (think of the Iwo Jima monument in Washington). Rather the artist created a spirit of meditation, activating memory. Our association with these distant figures stays in the present, our longing for just resolution. Said General Colin Powell in a ceremony of the centennial year, in 1997 before the Memorial: “Never has bronze spoken more eloquently.” The monument continues to challenge us at the nexus of the three trails, as people rush past in droves, some shelter in winter cold – but some also still stop and remember.

“Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory”

May 29, 2018

The Rev. Heather Janules

Travel up Beacon Street in Boston towards Park Street on any given day and one cannot help but notice – to see, to smell, to hear – the pulse of human life. People bustle from place-to-place in heavy overcoats or shorts and t-shirts, depending on the season, wearing the earnest attire of executives and the carefree clothes of tourists. The Massachusetts State House looms over the Common, regal in its civic formality, its granite steps serving as a regular dramatic stage for gathered protesters. Buses park to dislodge passengers, taxis speed by, traffic stops and moves again with the regular rhythm of the stoplight.

With so much life in this corner of the city, it would be easy to miss the Shaw Memorial, the bronze relief statue created by Augustus Saint-Gaudens depicting the 54th Regiment and their commander, Robert Gould Shaw, directly across the State House steps. And thus it would be easy to miss the story it tells, a story that recounts the Civil War, a painful chapter in our nation’s past, while also inviting us to consider the racial struggles of our own time. How I wish we were there, now, in its presence, as we consider its meaning. As that is not possible, we must rely on photographs, reprinted in your orders-of-service, and a little imagination.

I thank Nancy Scott for sharing her deep knowledge of the Shaw Memorial with me and with all of us this morning. Having now explored the statue’s history and symbolism, I emerge with a better understanding of this enduring piece of public art. I believe the power of this memorial rests in how we consider sight – what we see in the statue, what the figures in the statue seem to point to and where we place ourselves in the vision it depicts; unity across lines of race in service to collective freedom.

There might never have been a Robert Gould Shaw Memorial as Shaw might not have served as commander had it not been for the insistence of his mother, Sarah Sturgis Shaw. Sarah and Robert Gould Shaw’s father, Francis Shaw, are remembered as, in the words of Polly Peterson, “radical Unitarians who were among the first to embrace Transcendentalism, feminism, and abolitionism.”[2] When abolitionist governor of Massachusetts, John Andrew, asked Robert Gould Shaw to lead the first black regiment, Shaw first refused as he hoped for more conventional and promising military opportunities and did not share the intensity of his parents’ zeal for social integration.

But, as many of us know, mothers can be persuasive. Upon hearing of her son’s decision, Sarah Shaw announced that, “this decision has caused me the bitterest disappointment I have ever experienced,” that had her son accepted this assignment, “it would have been the proudest moment of my life…I could have died satisfied that I had not lived in vain.”[3] Through her influence, Shaw changed his mind.

The Regiment was assembled through enlisting African American volunteers throughout the north. Frederick Douglass was an enthusiastic recruiter, proclaiming to fellow black men, “I urge you to fly to arms and smite to death the power that would bury the Government and your liberty in the same hopeless grave. This is your golden opportunity.” Douglass’ sons, Lewis and Charles, joined the Regiment and fortunately survived the war.[4] In retrospect, one Regiment veteran articulated his motivation as not a wish “to fight for his country…but rather to find his country.”[5]

Public opinion was cool to the idea of black soldiers. But curious citizens watched the men train and drill together, growing in confidence and competence. By the time the Union soldiers marched up Beacon Street, they met enthusiastic crowds.

Shaw and the Regiment were principled men. While the Union invited these newly-freed African American citizens to risk their lives in battle, the government refused to pay the black soldiers the same as white. Shaw frequently wrote letters of protest and encouraged the men to refuse all pay until they received equity. In addition, Colonel James Montgomery ordered the Regiment to loot and burn a vanquished town in Georgia, an order to commit a war crime. Shaw and the 54th refused to participate.[6]

Shaw and the Regiment were also brave men. On July 18, 1863, they launched a raid on Fort Wagner, a nearly impenetrable installation. The mission failed, with 256 men dying or sustaining injuries. Shaw himself was one of the fatalities, his body interred in a mass grave with other members of the Regiment.

But despite the losses, they found meaning in the fact that the Union flag never touched the ground. Despite being shot four times, William Carney carried the colors to safety, an act that later earned him the Medal of Honor. He was the first black soldier to be so acknowledged.[7]

Those on both sides of the war who heard of the bloody battle admired the Regiment for their courage. Respect for Shaw and the Regiment’s valor inspired support of black regiments, equal pay for black soldiers and, in time, creation of the monument.

Perhaps the most poignant viewing of the memorial took place at its unveiling on Memorial Day, May 31st, 1897. A grainy, black-and-white photograph illustrates the survivors of the Regiment, slowly moving up Beacon Street to review Saint-Gaudens’ work, retracing the path they once took before cheering crowds as they began their journey south. As the dedication is remembered, “the bent, grizzled veterans (one with a pathetic carpetbag) march past the monument…[they] pause and gaze tearfully at themselves as young men, filled with ‘the hope and vigor of youth,’ marching toward some still distant Shangri-La of solidarity between black and white.”[8] Through viewing the monument, some aperture of time opened and they returned to see again the men they once were, united in seeking to achieve the impossible.

William James was invited to offer the dedication speech. James, a pacifist, was an unlikely candidate to speak at a war memorial. His own brother suffered from Civil War wounds which led to his premature death. James also recognized his inability to authentically speak to the black survivors of the war. Thus, James engaged Booker T. Washington to also address the dedication crowd; the two worked together to create words fitting for the moment.

After James’ speech and an enthusiastic rendition of The Battle Hymn of the Republic – a song written by another Unitarian abolitionist, Julia Ward Howe – Washington made his address. He names the veterans themselves as a symbol of Shaw’s enduring legacy:

To you who fought so valiantly in the ranks, the scarred and scattered remnant of the 54th regiment, who with empty sleeve and wanting leg, have honored this occasion with your presence, to you, your commander is not dead. Though Boston erected no monument and history recorded no story, in you and the loyal race which you represent, Robert Gould Shaw would have a monument which time could not wear away.

Washington’s emphasis on the men of the 54th is important as, despite this public gathering to celebrate the leadership of an integrated regiment, white supremacy defined the moment, with only the names of white officers killed-in-action inscribed on the monument and Washington’s presence as a cultural interpreter an afterthought.

Washington continues by naming the goal these men sought to achieve as work undone, as “not victory complete.” He defines this goal as not only the social liberation of the black man – he only spoke of men – but of spiritual liberation as well, of freedom from enmity towards whites, as the white man finds liberation from his own racial prejudice and greed.

Washington concludes with a clear articulation of his vision, grounded in unity and equity for all, what would be “victory complete.”:

One of the wishes that lay nearest Col. Shaw’s heart was, that his black troops might be permitted to fight by the side of white soldiers. Have we not lived to see that wish realized, and will it not be more so in the future? Not at Wagner, not with rifle and bayonet, but on the field of peace, in the battle of industry, in the struggle for good government, in the lifting up of the lowest to the fullest opportunities. In this we shall fight by the side of white men, North and South. And if this be true, as under God’s guidance it will, that old flag, that emblem of progress and security, which brave Sergeant Carney never permitted to fall on the ground, will still be borne aloft by Southern soldier and Northern soldier, and in a more potent and higher sense.[9]

Since that Decoration Day in 1897, the memorial to the 54th Regiment and Robert Gould Shaw has stood on Beacon Street, facing the State House. As Nancy named in her reflection, this places the monument among the people, an image of racial unity perpetually engaging our elected leaders instead of looking down upon the city. In this subtle way, the monument is a piece of activist art, not only doing the work of a war memorial by retelling history but making a statement about what was and what should be present in our collective practice of democracy.

Historians also invite us to consider the meaning of how Shaw and the Regiment are depicted. Saint-Gaudens could have sculpted an image of the hopeless but valorous battle at Fort Wagner but, instead, chose to illustrate the Union soldiers on their way to war, marching together. And, while creating an image of them in military formation, Saint-Gaudens could have designed the memorial with the men marching up Beacon Street, as they did so many years ago, instead of down the hill.

While Nancy observes that the natural tendency is to view from left to right, as we read, the result also renders the monument an image of magic realism – an image of all the men, including Shaw, returning safe from war. Thus, when the monument was unveiled and the veterans of the 54th marched along side, they viewed not only images of how they once were but also what could never be, their commander and their comrades-in-arms home and whole again.

This invites us to imagine other moments of magic. Charles Karelis, in his essay, “The Problem of Racial Hierarchy in the Shaw Memorial” challenges assumptions that Saint-Gaudens viewed Shaw and the black soldiers as equals; the realism of the soldiers’ likenesses derives more from the style of the era than from Saint-Gaudens’ conviction in their humanity. Even Shaw himself embodied the paradoxical stance of many wealthy white Unitarians of his time – advocating for the full citizenship of black Americans while also harboring views of white superiority. Thus, Karelis concludes, the Shaw memorial is radical only as it speaks to:

…the procession of society…the Shaw memorial is progressive when we think about its horizontal organization and less progressive when we consider the way Saint-Gaudens organizes his elements vertically. This great work of sculpture is ambivalent, like Saint-Gaudens the man and like America itself at the time.[10]

Indeed, over the years the Monument has served to not only represent the patriotism and courage of the 54th and their commander but also the state of the nation’s vision in regards to race. As the monument degraded from years in the elements, reaching near-collapse before its restoration in 1981, the monument also seemed to reflect the contemporary state of the faith that motivated Shaw and the soldiers to impossibly band together and struggle for change. The Shaw memorial stood as a silent witness to busing, to urban poverty and segregation, contemporary legacies of the years of legal bondage, legacies we live with in our own time.

Perhaps the second-most meaningful viewing of the Shaw memorial took place not in the shadow of the Massachusetts State House but in Washington D.C., at the National Gallery of Art, the place where one of two replicas of the monument stand. Maureen Fallon contacted the Gallery with a special request; her son, Lieutenant Timothy Fallon lost sight in both his eyes while serving in Afghanistan. Remembering Saint-Gaudens’ piece with appreciation, he wanted to touch the sculpture to experience it once again.

So, before Lieutenant Fallon relocated to Chicago for rehabilitative care, the Gallery arranged for him to have a private experience with the sculpture, caressing, in his words, “the faces of the dead warriors tramping into a hailstorm of fire and war.”[11]

Such is the intimacy between those who enter battle for a purpose greater than themselves. And such is the need to be reminded that this willingness to try the impossible does not go unnoticed.

In his last speech of his life, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. draws from Julia Ward Howe’s Battle Hymn when he speaks of the day that is to come: “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!” When he speaks of the “Promised Land.” King also acknowledges, prophetically, that he may not get there himself, these words spoken just the night before his assassination.[12]

If we pause and pay attention, we can observe the milestones of those who dared to strive towards right. And, as Howe illustrates through biblical imagery in her hymn, we can also pray for and sometimes perceive the dawning of an even-greater vision, an even larger love. Such is the work of memorials and such is the meaning of Memorial Day.

[1] A gilded wooden pinecone adorns the top of the golden dome, a symbol of the state’s reliance on logging in the 18th century. Today, the Massachusetts State House is one of the oldest buildings on Beacon Hill, and its grounds cover 6.7 acres of land.

[2] https://www.uuworld.org/articles/shaw-regiment-hope-glory

[3] Mehegan, David. “For These Union Dead.” Boston Globe Magazine, September 5, 1982.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_Henry_Douglass

[5] Duffy, Henry, J. “Consecration and Monument: Robert Gould Shaw, the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, and the Shaw Memorial.” The Civil War in Art and Memory, Kirk Savage, Ed. Yale University Press: New London, CT. 191.

[6] https://www.uuworld.org/articles/shaw-regiment-hope-glory

[7] http://www.historynet.com/william-h-carney-54th-massachusetts-soldier-and-first-black-us-medal-of-honor-recipient.htm

[8] Mehegan, David.

[9] http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/a-speech-at-the-unveiling-of-the-robert-gould-shaw-monument/

[10] Karelis, Charles. “The Problem of Racial Hierarchy in the Shaw Memorial.” The Civil War in Art and Memory, Kirk Savage, Ed. Yale University Press: New London, CT. 221.

[11] Anderson, Nancy. “For All Time to Come: Memorializing Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Regiment.” Tell it With Pride: The 54th Massachusetts Regiment and Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Shaw Memorial. Sarah Greenough and Nancy K. Anderson with Lindsay Harris and Renee Ater. Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, 81.

[12] http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkivebeentothemountaintop.htm

Topics: Memorial Day, Veterans